The following interview with Donal Ruane was conducted in May 2006 by Gyrus, and was first published in Dreamflesh Journal Vol. 1.

Gyrus: What strikes you as unique about the experience of ayahuasca?

Donal: It’s a difficult question to answer, as I get more experienced. The reason being that my experience of ayahuasca varies according to who I drink it with, and the brew. It appears to me that how the brews are made, and the additives that are used, and the set and setting in which it is consumed, very much alter the experience.

Last year in Iquitos I had a session with an Indian shaman from the Witoto tribe—a very interesting tribe who have had an awful history of exploitation and abuse, by colonists and by missionaries, who have devastated their belief systems and their way of life. They feature heavily in Wade Davis’ book, One River. I didn’t know much about them until I met this shaman, Don Mariano. He’s from Columbia, along the Rio Negro I think, one of the tributaries of the Amazon. He’s sixty-four years old, and he first started training to be a shaman, dieting with ayahuasca, at eight years of age. So he’s been drinking for a long, long time.

His ayahuasca was very different from the other brews I’ve drunk. My experiences are mainly with two types of ayahuasca. Initially it was with the Church of the Santo Daime, and then later I started to drink with Peruvian shamans.

Now after drinking regularly with the Santo Daime for a few years I started to feel increasingly restricted. I felt the experience itself and the brew itself was controlled and there was pressure to conform to their particular model and ultimately to become a member. The church itself was founded by Raimundo Ireneu, a black rubber trapper, after a period spent drinking ayahuasca in the jungle where he received instructions to found the church from a female spirit who he associated with the Virgin Mary. Ironically enough, Ireneu himself was probably initiated into the use of ayahuasca by a Peruvian mestizo shaman. Of course, the Santo Daime only works within a certain spectrum of what is possible with ayahuasca. This is not necessarily such a bad idea; ayahuasca has the ability to manifest some pretty dangerous phenomena. Let’s say that of all the hallucinogens it is one of the more unpredictable.

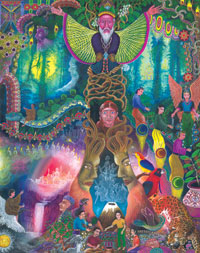

Don’t get me wrong, I am enormously grateful to the church. However, as is often the case with such matters, a synchronicity nudged me in another direction. The day I bought the book Ayahuasca Visions I also met Pablo Amaringo for the first time, coincidentally, in a London art gallery where I had gone to meet a friend. Out of that initial meeting, my friendship with Pablo developed so much so, that I decided to visit him in his hometown, Pucallpa, four months later. During that first visit, while talking to Pablo, I realised there was a lot more to learn about ayahuasca than I could possibly learn in the context of the church. The ritual use of ayahuasca in the Upper Amazon region has developed over millennia into a sophisticated science, a plant alchemy with a remarkable mythology of its own.

Now there is a big difference between the Santo Daime brew and the traditional ayahuasca drunk by shamans in Peru—it’s a lot less visionary and isn’t as purging. You don’t enter the remarkable visionary realm, and you don’t get the ‘drunkenness’ which you normally associate with ayahuasca in Peru, which they call mareación—a Spanish word which translates as ‘sea-sickness’…

This is what William Burroughs talked about as “the motion-sickness of time travel”…

Yeah, he talked about it that way. It’s something that comes on usually within about two hours, but it can come on at different times. Usually you start feeling very nauseous, then your body heats up. I usually sweat and yawn profusely; it’s very uncomfortable and unpleasant. At this stage you become very disoriented, and you may vomit, sometimes in conjunction with diarrhoea. They can be separate, or you can get the two of them together. The mareación usually lasts about half an hour, three quarters of an hour, but again there’s no standard. Now you don’t tend to get this with the Santo Daime brew, and you don’t get the visions. Of course the Santo Daime is always drunk with the lights on, and traditionally ayahuasca is always drunk in the dark.

The other ayahuasca I have most experience with is what I call Pucallpa ayahuasca, which is like ‘moonshine’. That’s the standard ayahuasca recipe, which is made using the bark of the vine Banisteriopsis caapi and the leaves of the bush Psychotria viridis—alone. They do put additives in it, but that’s to do with particular shamans’ own likes and dislikes. Some of these additives are psychoactive, but other aren’t. For example, plants like coca have quite subtle effects compared to something like Brugmansia (which they call Toé), which is similar to Datura but in fact isn’t—although it contains the same tropane alkaloids. Some shamans use Brugmansia on its own, usually by smoking the leaves.

The ayahuasca of Don Mariano had Banisteriopsis caapi, Oco yagé (Banisteriopsis rusbyana), mapacho tobacco (Nicotina rustica), and two leaves of Toé. The Oco yagé would have been the substitute for Psychotria viridis. I only found out later that it contains 5-MeO-DMT, so it’s not very visionary. I got some slight hypnagogic visions, but not many. I originally thought that ayahuasca’s a “visionary” vine, so if you don’t get visions, you’re not getting proper ayahuasca. But while that one didn’t give many visions, it was an incredibly powerful teacher—probably one of the most powerful experiences I’ve had.

Each brew has its own personality. This one was very talkative, and it was very purgative too, due particularly to the tobacco additive, which made me really nauseous and gave me diarrhoea; I got both. And because of the Oco yagé, it lasts over six hours, rather than the average four hours.

They say that Toé and Oco yagé are “teacher” plants; the brews are less visionary, less about power and more about receiving teaching. That’s what I received: a very, very powerful teaching. I was literally talked to for four, five, six hours. Almost from the time it came on this telepathic dialogue started, which is one of the phenomena we get with ayahuasca. What it is, I’m not sure; there are many theories. The locals call these phenomena “spirits”. McKenna called it the Logos and connected it with Philip K. Dick’s creature of pure information that we find in his extraordinary novel Valis. I’ve been drinking and studying this for about seven years now, and I’m still trying to understand all these phenomena.

When I first came across Pablo’s paintings I had never before seen an artist capture the visionary realms in such a startlingly original way. I was captivated not only by the visions themselves but also by their paradoxical nature… so vividly alien, and yet so extraordinarily familiar and beautiful. I wondered, where are these dimensions located? Pablo explained to me that he had visited many such places, many universes when he drank ayahuasca. He said, “I have visited the Moon, I have visited Mars, I have visited Jupiter, yes, all the planets. There are many planets. I have visited all of them. There are many spirits in these places. There are sacred temples, places like islands with castles. In these castles some spirits are good but some are bad. They have human faces but their body is of a tiger or a snake or an eagle.” Pablo told me that shamans learn to immerse themselves in these domains and interact with the spirits like actors in a film. This only happens after dieting and drinking ayahuasca for a long time—so that you no longer see visions as if you are looking at television but are completely immersed in them.

How could this be so? How could so-called ‘primitive’ people and peasants have developed such a sophisticated methodology of interaction in these ‘virtual realities’? Jung speculated that “it may well be a prejudice to restrict the psyche to being inside the body. There may be a psyche outside the body, and one has to get out of oneself to get there.” He further speculated that this ‘psychic reality’, rather than being two separate worlds, one inside and one outside, was in fact two aspects of the same world: a microcosm and a macrocosm. This has very much been my own experience. For ayahuasqueros the difference between the purely mythological and what we would consider ‘real’ is indistinct.

In fact, the only way to really understand these ‘invisible’ realms is through metaphor: the secret language of the shaman. What we are talking about here is a way of seeing, a method of perceiving ‘reality’ differently. For the ayahuasquero the tobacco smoke from his pipe becomes a vine which becomes a rope which becomes a snake which becomes a ladder to climb into other worlds. The anthropologist Graham Townsley, while working with Yaminahua ayahuasqueros in the Peruvian Amazon, was told they called this “language-twisting-twisting”. For example, arkanna is a Quechua word meaning “to block” or “to guard”. It can be an icaro, a magical song, or an object like a crystal or an animal that the shaman puts inside you to protect you. Or it can be tobacco smoke blown over you to form a protective shirt or armour, like a bullet-proof vest. The relationship between the signifier and the signified is fluid. For a child, a chair can very easily become a flying saucer; a simple stick a golden sword that defends against evil knights. As one gets older this imaginative engagement with the mysterious potential of the universe is ‘unlearned’. The child is literally programmed not to see in this way from a certain age. Children who continue to see in this way, who refuse to give up their secret friends, are usually considered ‘deviant’ and treated as mentally ill. What we are talking about is really a technique for ‘seeing’ that we in the West have lost! A technique that enables one to view ‘reality’ as a constantly unfolding mystery… an interconnected domain of wonder, rather than the ‘objective’, fragmented view we usually perceive.

As a child growing up, I heard many stories of ‘seeing’ fairies among the old people in the west of Ireland. When I asked them where the fairies were now they always said the same thing: electricity and cars had driven them away. What really happened of course was that people stopped seeing fairies because of the paradigm shift overtaking the wider community at that particular time. The influx of new technology required a radical shift in the belief systems that had sustained that rural peasant community for thousands of years. Beliefs, which included a reciprocal relationship with nature spirits, were literally unsustainable in the ‘light’ of the electric bulb. The new magic had destroyed the old… and people gradually stopped seeing and believing in fairies. Which in my view is a great shame.

Another factor in this was the gradual encroachment by civilization on the wilderness; cars and electricity made the areas where these beliefs still existed more accessible, and he introduction of radio and television and the electric light literally lit up the darkness where these beliefs existed, ironically making them invisible once more. I love Patrick Harpur’s idea, which he expounds in his wonderful book Daimonic Reality, that the unconscious was formed during the Reformation. He speculates that the Anima Mundi, the World Soul, was withdrawn from outside and relocated within, as the collective unconscious, eventually to be rediscovered by 20th century depth psychology. In effect, the daimonic realm was forced underground into the unconscious regions of the mind at the beginning of the Age of Reason, when the mind became identified with reason.

I’ve had a lot of what I would call “archetypal experiences”, encounters with archetypal beings and phenomena. A lot has been written about this, but I don’t think there’s been as much work done on just steadily studying how and why archetypes manifest, what they are, and how our experiences of them vary over periods of time. What do these experiences actually mean?

Anyway, something else I find remarkable about ayahuasca is the purging aspect. One thing I noticed around Pucallpa is that they call all the plants La purga.

All the ingredients of ayahuasca?

No, all the different plants that shamans diet with, the teacher plants within this “science”. The science has various names. For instance, an old name that Pablo used was alquemica pallistica, which means “tree alchemy”. There’s also ciencia vegetal—a mestizo term meaning “plant science”—and ciencia de los palos, “science of trees”. A very old Quechua term is caspi yachai (“tree wisdom”).

What we’re talking about here is a form of alchemy. My theory is that this so-called “plant science” is in fact the ancient precursor of medieval alchemy. I think the Spanish named it this when they came over because they recognized what was going on.

In the same way that the Catholic communion must have been seen by the conquistadors to be “primitively” echoed in the mushroom cults of Mexico, where they called the mushrooms “God’s flesh”.

Exactly. And this science believes that a certain number of plants-some obviously psychoactive, some not-each have a “mother”, some sort of ancestor relation. They also use the terms father, or grandmother or grandfather in this sense. These are the owners of the plant, and these owners can be reached by going through a strict diet of purification and consuming the plant in isolation.

I’ve dieted with ayahuasca, but I’ve also done a eight-day diets with plants that are not psychoactive. For instance, the “jungle onion”, cebolla de selva (or cebolla de monte), is referred to as a purgative, and it did make me vomit the first time I drank it. Tobacco does the same thing. I think all the plants have a purgative effect.

But not necessarily to the point of inducing vomiting? Perhaps more just detoxifying?

Yeah, making you sweat or whatever. They flush things out of you. To me the whole point of the science is a purification of the body, in order to communicate directly with these plants and learn things from them. And this is done over periods of time. It requires isolation from people: no conversations, no looking at people, and no people looking at you. Sitting alone, eating a special diet: no salt, no sugar, no pork, no alcohol, no sex. In fact, traditionally you eat only boiled plantain with a small number of fish-interestingly enough, fish that only eat plants. There’s boca chica (a type of snapper), palometa (related to piranhas), and sardinas.

With some of the plants, particularly the trees, the diet is even more important because some of them are highly poisonous. It’s much more dangerous to not go with the diet with those than it is for, say, ayahuasca. It’s interesting that purifying the body allows you to ingest “poisons”…

So some things we consider inherently poisonous may just have bad reactions with things we habitually consume.

That’s what it seems to be. One of the people I got to know and interview was an old shaman called Don Fidel Mosombite—who incidentally first turned Terence McKenna onto ayahuasca in the mid-1970s. He has been a practising ayahuasquero for over fifty years, and has dieted with a lot of plants and trees. One of these was the catahua tree (Hura crepitans). He told me he dieted with this tree for three months. He had to drink the sap of this tree once and he was intoxicated for three days. He said he thought he was going to go insane! During this time he had an experience where he was suspended by a rope upside-down from a steel pole, rather like the hanged man in tarot. During this he was cut loose and started to fall, and if he hadn’t dieted well he would have been killed. Just before he hit the ground he suddenly transformed into the commander of a ship which was travelling underwater. This was the catahua ship. Then a voice gave him instructions on how to smoke the leaves of this tree in order to heal people.

We take the word ayahuasca and put it on our Western list of psychedelics. Do you think that creates a false impression of how it works, and that it should be seen as embedded with the entire ciencia vegetal, this whole belief system revolving around spirits and their various plants?

The whole molecular level of nature is connected with spirits in this science. The scientific categories we have broken things down into, they have personified.

Do the key constituents of ayahuasca—Banisteriopsis caapi, Psychotria viridis, etc.—do they have a special role in the “pantheon”?

Different shamans have different views. Graciela said that the jungle onion, and Ajo Sacha, which is jungle garlic, are much more important than ayahuasca. That they’re much more potent for healing. But what Pablo said to me is that ayahuasca is at the centre of the whole system. Usually you go from ayahuasca to the other plants—though this isn’t always so.

There’s different ways they heal, specific to the plant. Take plants like Sangre de drago [Dragon’s blood, Croton lechleri], or Una de gato [Cat’s claw, Uncaria tomentosa], which have particular effects. They’re medicinal herbs. Dragon’s blood is phenomenal for congealing cuts.

But there is also a lot of magic involved in this science. For example, it is believed that by blowing an icaro into a glass of water and getting the patient to drink, it will cure a wide range of illnesses.

Could you talk more about the effects of ayahuasca in relation to this system?

My experiences with it don’t fit the materialist view of how it works, which says that you take certain plants, mix them together in certain amounts and you get this effect. In terms of dosage, you can take more and not have a very strong experience, or take less and have a much stronger experience.

I feel there are realms made visible by ayahuasca that are to do with the plant itself; but there also appear to be realms that are all around in the jungle—and I don’t know what that’s all about. Because that doesn’t fit our paradigm. I’ve had experiences of ghosts, all sorts of different presences, little dwarves or whatever, that they connect with different plants, different phenomena out in the jungle. They seem to be things connected with place. I don’t have those experiences when I’m drinking here in London. Having all those trees around you, it seems to open up another level of the experience.

What is made visible here in your flat? Or is it a more interior experience?

It’s just a more interior experience. One of the things they say is that the further away from humans you are, the more pronounced the experience is. To get really in touch with spirits, you have to be way out in virgin jungle. I’ve never done that, but I’d love to. Certainly the city isn’t a very pleasant place to be when you’re opened up like that. It’s not that there aren’t all sorts of energies or spirits around in cities…

Maybe ayahuasca just isn’t the best way to approach them.

It comes from a particular place, and it’s connected with that ecology. And that seems to be the realm that it opens up.

Something I also wanted to mention about the varying effects of dosage is that shamans appear to be able to “take it out of you” after you’ve drunk it-by either blowing you with tobacco, or rubbing you with aguardiente, which is sugar cane rum, and camphor.

Like a magical thorazine?

Yeah, it doesn’t make sense. It’s been done to me, and it very obviously did happen. That was a time when I’d only taken half of what I’d done the night before, but it really was quite ferocious. They often sniff ayahuasca and see it as having an effect, y’know?

And you think this is beyond “set and setting”?

I think it is beyond that, I think there’s a magical element to it, and I don’t really know how it works. Maybe it is set and setting, maybe set and setting and intention are that powerful. Maybe intention is that powerful, and when you put it together with ayahuasca, it multiplies its power by a million, like putting a magnifying glass over it. You have the sun, and a piece of paper, and with the magnifying glass it bursts into flames. Maybe that’s what it does to the intention: it ignites it. But there certainly seems to be an aspect to it that I can’t understand, a magical element.

Could you back-track to the vomiting thing? You talked about it being called La Purga. In our culture, vomiting’s associated with eating disorders, being too drunk, basically a pathological thing—undignified.

From the first time I witnessed it, it did completely throw me. The diarrhoea as well. It was very casually dealt with. I also saw people doing that after smoking pipes of tobacco—vomiting and diarrhoea. But they also have a thing about spitting as well, which we have a taboo against.

The healing process is about purging the body. And they use plants that purge the body, that make you spit up phlegm, which make you vomit and have diarrhoea, and sweat. That’s four ways of getting toxins out of the body. That’s usually in conjunction with dieting, which means that you’re also reducing your intake of toxins.

So, similar to alchemy before the point when magic and science separated, what they’re practicing here is a quite sophisticated “nature science”, knowledge of plant properties and so on, but completely intermingled with what our culture would call “superstition”. For them it’s part of the same system.

The way I understand it is that it’s a metaphor anyway, and the goal that’s produced out of alchemy is spiritual enlightenment—personal mastery and immortality.

What form of immortality do they see it as?

All shamans believe they live on in spirit form after they die.

Reincarnation?

Ordinary mortals keep on returning to the material realms until they work everything out they have to. Shamans, on the other hand, depending on how advanced they are, because of the spiritual work they have done through the suffering of the dietas, believe they become pure spirit and live on eternally. Death is not the end, basically. There’s a lot to be said about the whole psychedelic experience being a preparation for death. And that resonates for me.

The whole idea of making gold out of shit, as it were, I can see happening in the dieting, in purifying the body, vomiting and diarrhoea, getting rid of the toxins and pollutants. But also all the psychological stuff as well. I was releasing angers and resentments, and releasing memories, phenomenal memories. This wasn’t when I was on ayahuasca, it was dieting the day after. Just sitting there and remembering kids I went to school with, all this sort of stuff. It was like my memory banks were completely opened for the first time. I suppose rather like what we are told will happen at the exact point of our death—confronting all our past deeds.

One of the more startling experiences I had was when two entities in a canoe confronted me. They were like aliens. I’d just travelled through this awesomely beautiful multi-coloured golden city, and they told me that the Spanish never found El Dorado—that this is it. That the extraordinary experiences that ayahuasca can make available to us if we follow the proscriptions of the diet were in some way a secret fount of knowledge and teaching, connected with immortality, that humans could make contact with—and have been making contact with it for thousands of years. That El Dorado was a metaphor that the Spanish mistook for a literal truth. There never was any golden city in the jungle. I suppose this is an ongoing problem humans have had interpreting mythology, including the Bible—taking it literally. Metaphor is, at its simplest, a way of interacting with the ‘other’, with the unknown.

One of the more startling experiences I had was when two entities in a canoe confronted me. They were like aliens. I’d just travelled through this awesomely beautiful multi-coloured golden city, and they told me that the Spanish never found El Dorado—that this is it. That the extraordinary experiences that ayahuasca can make available to us if we follow the proscriptions of the diet were in some way a secret fount of knowledge and teaching, connected with immortality, that humans could make contact with—and have been making contact with it for thousands of years. That El Dorado was a metaphor that the Spanish mistook for a literal truth. There never was any golden city in the jungle. I suppose this is an ongoing problem humans have had interpreting mythology, including the Bible—taking it literally. Metaphor is, at its simplest, a way of interacting with the ‘other’, with the unknown.

What about the identity of the “spirit” of the plant, or plants? McKenna has his thing about “the Mushroom Voice”. Whether you see the psilocybin mushrooms as being seeded from space, as McKenna suggested, or having evolved on Earth, genetically it’s a distinct entity in nature. Ayahuasca, however, doesn’t exist without humans. The constituent plants exist of course, but we’re talking about an admixture that’s an artifact of human culture.

If there were no humans, I don’t think this realm could exist. Because the third ingredient along with the two plants is human consciousness. That realm is some sort of common ground—Jung would call it the collective unconscious. It’s also a realm where you can meet other shamans and mystics and so on, and where shamans have fights. And it carries over into dreams.

It seems that an awful lot of revelation comes through in dreams, during or after the diet. And that’s the most understandable, clear information coming through. Certainly the combination of the dieting, the plants you use, and the tobacco you smoke, enhances and incubates dreams in combination with isolation from the normal everyday familiar world of human interaction. Being deprived of status and normal social relations focuses the mind into the now. The initiate is ‘betwixt and between’, a liminal state where revelation can take place.

Many people may think that the key to this mestizo shamanism is the visionary experience of taking ayahuasca.

Sometimes the visionary experience is superfluous. Often the more interesting stuff can happen just after, or a period of time after you drink ayahuasca. I think it stays in the body; particularly if you keep on dieting, it’ll stay in the body longer than normal. After drinking for months in Peru, when I came back I’d say there was still ayahuasca operating in me for up to a year afterwards. I brought up an awful lot of things, negative things, and it appeared to teach me about my depression… which then, over time, transformed into something else. Something I could understand. Something I had control over. This happened after I came back from Peru. It was a very difficult period, for a few months, where it kept coming back. It appeared to be showing me how it worked: this is how it works, and you have control over it, you don’t have to be a victim of this.

Ayahuasca to me is a harsh teacher. It expects an awful lot of you, and if you don’t learn the lesson, it can push your face in it. There are many stories in the mythologies around Pucallpa of the bad sides of ayahuasca—as much as it can give you good things, it can give you bad things. It can make you lazy, lethargic, it can destroy your life. It can cause illnesses, if you go against it. It is believed that if you diet badly, it punishes you. Instead of doing good, it does harm to you.

If you mix different plants, it gets jealous. It is conceptualized as having all the characteristics of human beings by the shamans who use it, including anger and jealousy. There appears to be an almost sexual relationship going on between the shaman and the plants, and the spirits of the plants are very jealous; you’re not allowed to mix plants. For example, when I was dieting with this jungle onion, I wasn’t allowed to drink ayahuasca for three months afterwards. I couldn’t even smell it, Graciela said, because they get jealous when they get mixed up.

Many of Pablo’s experiences, being attacked by sorcerors, have happened in his dreams, when he wasn’t using ayahuasca at all. When you do drink ayahuasca, especially when you’re dieting, you tend to have very light sleep, very “lucid” sleep, where you’re almost awake.

You’ve said of Western anthropologists who have taken the plunge and partaken of ayahuasca ceremonies, that that’s all well and good, but that actually the literature misses some of the more important effects you only get after a prolonged initiatory experience. What have we missed?

Well, I haven’t experienced anything that I haven’t heard anyone else talk about; but in the main field of anthropology, it tends not to be talked about. In Jeremy Narby’s book Shamans Through Time, there’s an anthropologist called Edith Turner who talks about seeing these ghostly figures coming out of a person being healed, and I’ve seen phenomena like that.

What convinced you that this was something other than an hallucination? Not that it’s not “real”, but that there’s not much that people haven’t seen when taking strong psychedelics!

Because I wasn’t intoxicated enough at the time. These experiences happened before or after taking ayahuasca. I’ve seen enough hallucinations to know this wasn’t that. “Hallucination” is a very problematic word anyway.

I’ve seen smoky figures standing over sick people, presences around me while I’m drinking. These were there, with your eyes open. I’ve also seen figures sitting in the trees, watching while I’m doing ayahuasca, which are transparent, like the creature in Predator. Like silhouettes of crystal or glass.

The word “shade” comes to mind…

Yes, that’s an interesting word. On the borders, betwixt and between. That’s where I’m at. To me there’s many levels of hallucinations; I’ll have to start cataloguing it to figure it out. There’s the full-colour visions that you see on ayahuasca, very fast, with your eyes closed. There’s another level of figures you can see, like the snakes I saw here on the floor, which were so realistic I nearly tried stamping on them! On that level I’ve seen figures come to me and hand me things at the beginning of sessions. A few weeks ago, actually, a figure came to me and gave me a glass of beer; I don’t know what that was about because I don’t drink any more…

One of your ancestors!

One of my demons… When I had the very powerful mystical experience with Don Mariano, these Shipibo women came and put books on a table in front of me. They were communicating to me using sign languages. I’d call them “hypnagogic”, dream-like. The sort of phenomena I associate with mushrooms or acid.

Then there’s all the aural stuff, voices speaking to you, and your psyche dividing into parts. That could account for the spirit phenomena, but I’m not sure. You get a chance to see your fears and neuroses, your own operating system, but detached from it to observe how it works. How it creates your sense of self in the world, and how it creates the world you perceive and experience.

Jung described individuation as separating out the distinct parts of yourself…

That’s certainly what I’ve observed in my work with ayahuasca. There are many levels to working with it. There’s the idea of “plant teachers”, and the idea that it’s like university, with a hierarchy of levels of understanding, moving upwards all the time. I had a huge breakthrough experience last year in Peru and it became so different from my previous experiences. I had a lot more confidence with it, and I learned how to deal with a lot of my fears. I also know that’s not the end! I know that when you reach a certain level, you level off; then suddenly you go boom and you’re moving up again. That “jumping up” is quite a challenge, and can be quite traumatic, because it opens up a whole new realm.

You sense that these levels are governed by the experience itself, and only loosely tied to human traditions?

Yeah. If you keep on working with it, it brings you to different levels. That’s an alien idea for us: that plants could be enabling something like that, that they could teach us.

That they could do anything but just sit there! Could you talk about icaros a bit, the magical songs of the ayahuasqueros? Is that specific type of tradition unique to South American ayahuasca use, or do they have similar things in Central American mushroom use, in Siberian shamanism, or whatever?

I’m not as familiar with the other traditions. I know singing itself is definitely a part of all shamanic traditions. Being a shaman is often equated with the ability to sing, and without songs you are not a shaman. One of the things that I thought was interesting was if you compare Shipibo shamanism with mestizo shamanism. Mestizo shamanism is about 150 years old, and it was learned by people of mixed blood, people from Europe who left the cities to work as rubber trappers in the jungle around Pucallpa and Iquitos. They got ill and went to indigenous Indians and learned about ayahuasca. With mestizo shamanism, you mostly learn songs from your maestro. Some of them can be received, but a lot are handed through family members. Often the songs that are believed to be most powerful are those in different languages: Quechua, Campa, other Indian dialects. It’s the reverence for the Other. You find that again with gringo spirits that appear to mestizos; it’s something from outside your own culture that has power. But for the Shipibo there isn’t this tradition of handed-down songs. The songs they sing are always improvised on the night of the session.

Unlike most other shamanic traditions, they don’t really have “objects”. They have a pipe, and bottles of aguardiente, medicinal plants and stuff. They might have rattles, but these would usually be made from the leaves of the piníon tree. Their basic tools are blowing their pipe tobacco, maybe certain perfumes… and icaros.

When I was dieting I would get repeating nightmares, hag-ridden kind of experiences, very terrifying. After a period of time I would start singing songs when these came up. There’s a whole vocal aspect to these experiences for me. I was waking up and going [lets out a strained high-pitched sound]. At the time this seemed almost like trying to scream, or trying to articulate the terror I was going through-which often woke everyone in the village up! But over a period of time, those high-pitched sounds became the songs I had been learning while drinking ayahuasca. It wasn’t conscious, it would just come out, until someone woke me up.

The other way I received icaros is directly through the mareación, the ‘sea-sickness’ phase of taking ayahuasca. You get very dizzy, very hot, your body boils, you’re sweating, it’s very uncomfortable. You also start yawning and yawning, and the more you yawn the more tired you get—you feel like you’re falling asleep or going unconscious. Melodies came to me spontaneously, having that experience. I don’t know where they came from, I would just start singing.

Graciela Shuna

Later, Graciela taught me how to put words to them. They have particular phrases in Quechua, which are in all the songs, and which are almost interchangeable. They’re all about calling the doctors, calling the magic, giving power, asking for power from the plants, etc. A lot of the songs have the same sort of words and phrases, with different melodies; the same phrase is repeated over and over again. Those phrases are important, but it seems to me that they’re not as important as the melodies. Once you have the melody, you have power from it, because you have something you can use.

When I was dieting with the jungle onion, on the first night after drinking it, I had this incredibly vivid dream where this very powerful man came. There’s all these images of power they have; they talk about doctors, policemen, presidents, kings, queens, commanders in the army. Often I had dreams about powerful people. In this dream it was a kind of trickster, a very powerful, rich businessman. I didn’t trust him. He was doing a deal with me, and he was taking me somewhere in a car with three other older men. He was sending me into this building that was falling apart. All the floors were damaged by water, very weak in the middle. A beautiful old house, with beautiful designs on the walls. When I got to the top room I started falling through the floors… down, down, down. But it wasn’t frightening. There was a brass band playing a waltz, and I started singing along with it spontaneously. All around me, as I was going down faster and faster, were all these beautiful dancing designs, like ayahuasca visions, beautiful patterns… I was amazed.

Of course, I woke Graciela up; she was sleeping beside me, and I was singing my head off! “Donal! Donal!” [laughs] She interpreted the powerful man as being the father of the plant. He was coming to teach me something, a Shipibo icaro. And the beautiful designs I was seeing were the songs: the designs were the visual manifestation of the song.

What is the nature of the power of icaros?

It’s having a relationship with something that’s outside yourself, but also within yourself. By learning about that and engaging with that, you learn something, and you get power. You’re powerful by the fact that you’re relating in that sort of way.

Maybe related to the strength that a Jungian would see gained in integrating parts of the Self? Psychic integration.

Yes, exactly. When she started interpreting my dreams, I could see her pattern. Everything was interpreted in order to empower me. To show me that everything-all my experiences, all of my psychic life-was part of an interconnected landscape that I was now becoming familiar with and learning about. By engaging with that, and by being able to have a relationship with that landscape, that was giving me its own power.

There’s that paradox of relating to something outside you and inside you. And when we talk about “psychic integration”, the process is actually about separating things out, as figures, landscapes…

It is a funny one. It gets back to the idea of, “What the hell is an archetype?” They’re part of us, but they’re outside us as well. And everybody can engage with them, so they’re personal, but they’re also universal at the same time. It seems that there’s a space where they exist that’s both outside us and inside us.

There’s a fragmentation, but I presume for someone who’s insane, these parts wouldn’t be connected in any way. But when you’re in this altered state and you’re learning about it, it doesn’t feel like a part is going way over there and I’m “losing my mind”. What you’re doing is leaning about all these compartments of your consciousness. They’re like mirrors that are reflecting each other. You can observe consciousness itself at work, how it operates. You can see all these negative or problematic parts of yourself, and you can see how they work, and how they control. And you can also see how they don’t have to control you. It’s like Cubism or something, getting a chance to see it from loads of different perspectives. In that act of observing these parts of yourself, you get a chance to have power over them. It’s a slow process.

Obviously, once you have this understanding of what’s going on with yourself, you’re much more able to see what’s going on with other people, and help them.

It’s like the “theory of mind” in evolutionary thought, where self-awareness is seen to be at least partly initiated by the evolutionary pressure in proto-hominid apes to understand others. The pressure to act in a socially effective manner required having an understanding that something like your own self-experience is probably happening inside others. And thus, to understand, manipulate or empathize with others, you looked within, to make guesses about other people’s thoughts and motives, based on your own inner workings.

“Modular” theories of consciousness are also popular in evolutionary thinking now—seeing discreet types of intelligence, like social intelligence, technical intelligence and so on, as having evolved semi-independently. Obviously it’s different to the psychological “compartments” you were talking about, but interesting all the same.

You described the experience in concrete, spatial terms…

It does feel like the mind divides into these compartments. And one of those is an observer, watching the other parts. It’s separate from them. And that’s incredible. The fact that it’s separate. You see that they’re not integral parts of you—which is how you feel. You can feel your fears are you, but they’re not. They are, but they’re also outside you, and you can control them.

How did Graciela conceive of this, or is it just your experience? Was there part of her mythology that expressed that, and did she know what you were talking about when you related it?

No. I think it’s a Western thing. They have very different models. The whole issue is one of witchcraft and sorcery; it seems to me that they don’t have an explanation for negative experiences in altered states. Or, they do, but it’s an external one. All negative experiences in these states are rationalized as sorcery and psychic attack and so on. It’s not an aspect of yourself. Like paranoia, in the West would be seen as an internal thing projected out. Whereas they take it on as an external threat, and treat it in that way. But it works, what they do. It’s still a huge area that I expect to carry on trying to understand.

Another thing is the idea of voices that come to you. I don’t know what they are.

Disembodied voices?

It’s hard to say… It’s like what we were saying about the inner/outer division: for all intents and purposes, it’s ‘our’ own voice, talking to us. But it’s different. In one of the first experiences I had after drinking with Graciela, after she had gone to bed we had what appeared to be a telepathic conversation for an hour and a half while she was asleep in the next room. Among other things she told me that I could become a shaman. The next day she came and told me that I’d come and talked to her in her dreams, and that I’d thanked her for all she had done for me. A few weeks later during an ayahuasca session she said while in trance that the spirits had talked to her, and she confirmed the very things I’d been told that previous night by ‘her’. So she confirmed the conversation I had with her, about becoming a shaman.

I’ve had other conversations, and they’ve been quite extraordinary. If I’m rational, it can’t be spirits, because spirits don’t exist. Right? So it must be a part of myself. In some way, by dieting and drinking a lot of ayahuasca regularly, you break down your normal consciousness, and there’s a paradigm shift. And in that shift you gain access to a fount of information, the Logos, whatever you want to call it, and whole realms of beings. This feeds you information about all sorts of things. It can be predictive, it can tell you about healing people, all sorts of stuff.

What about songs being used to shape and guide the experience?

Yeah, and to take you to places. My experience of that is that the experience of drinking ayahuasca is too awful to contemplate without singing. The songs appear to be like roads, or some sort of guidance through what appears to be a chaotic experience. They’re guides through what can be an incredibly alien environment. That’s all I can say.

The beliefs around those songs are that particular plants teach you songs, and that that is a direct communication with the spirit of that plant. That plant is actually speaking to you through songs, and by having the song of that plant, that gives you the power of that plant to heal, and to protect yourself and so on. There’s loads of different types of songs: songs to take you to different places, songs to cure different illnesses, songs to modify the visions, songs to calm people down when the mareación is too much, songs to reduce the visions when they’re overwhelming and frightening, when you think they’re never going to stop… And then there’s the songs that are like “story songs”, which tell stories about the mythological experiences you can have: of going underwater and meeting mermaids, meeting the ghost ships, spirits of the jungle, etc. There’s songs with words, and songs that are just hummed, blown or whistled melodies.

Actually, icaro means “to blow”, and there a whole mythology of the breath of the shaman having power to heal. By smoking tobacco, you make the breath visible. That’s one of the reasons for smoking tobacco. The whole idea of blowing and sucking is found throughout South American: blowing for protection or to heal, or sucking out things like magical darts or whatever.

There’s a number of ways the tobacco works. They can blow out the smoke, and you can see it, the breath, the power, blowing over someone’s body. So that enhances the ritual, theatrical aspect. The other thing that comes out, which I find really interesting, is the “magic phlegm”. This is the phlegm that comes up from smoking tobacco.

A different view from our culture. We don’t call it the “magic phlegm”!

Very different. They call it the mariri, the magic phlegm, and only some shamans have it. It’s really weird how they get it. They get it through the diet, and it comes in the stomach, and then up, and it burns inside them… It’s difficult to understand. The shaman will bring it up, and he will suck the dart or whatever that’s causing the illness out of the person, with the phlegm in his mouth. That acts as a protection—so the arrow doesn’t go back into him, and cause harm to him. He holds it there, then he spits that phlegm out.

The other thing is that they use perfume. So they put a perfume in their mouth, suck something out of someone, and then tsssscccccchhhhh! they spit the perfume out. Again, the perfume protects. Or else they have the perfume and they blow it over someone as a fine mist, like blowing tobacco smoke.

The perfume stuff is fascinating to me. It’s also used to modify the visions. An apprentice shaman puts perfume on himself; so again there’s a whole sexual aspect of contact with spirits. You’re preparing yourself by putting on nice clean clothes and perfume before you drink. There’s also sniffing perfume when the mareación is coming on, to enhance the visions. There’s a whole olfactory realm, or spectrum, with ayahuasca, as well as the auditory aspect.

Do you hallucinate smells?

No, but you can modify the experience incredibly with smells. With the aguardiente, with camphor. There’s agua de florida (flower water), and Tabu, different commercial products that they use. I’m still learning about this, it’s such a big, big area. There’s been very little research on this. In talking to Pablo, it seems there’s less and less perfumeros around. There’s ayahuasqueros, tabaqueros, paleros (who are tree specialists), toéros (who work with Toé). And from what I can gather from Pablo, there’s very few perfumeros left. It’s a really sophisticated thing, the perfumes they make are really powerful. Shamans will go to a perfumero to get special perfumes to protect them from sorcery or to heal an illness. Like you might sing to create patterns around you for protection, he will do that with smell, with odours. Pretty wild stuff!

When using perfumes with ayahuasca, does the odour make a transition into visuals?

Yes, that’s one aspect. It also helps to calm you down, it can reduce anxiety. But yeah, you see the smells, absolutely.

On ayahuasca, you’re incredibly suggestible, so all these things are tools. By virtue of having an intention, you feel like you can make it happen. There’s certainly a kind of self-hypnosis; and by implication, you can hypnotize the person who you’re healing. And by doing that, by convincing them that you have this power and that you’re doing this, that by itself will enable them to heal themselves.

So it’s like Paul McKenna as well as Terence McKenna!

There’s all sorts of things going on there. I don’t like to use the term “placebo”, because people go, “Oh yes, placebo, I understand it.” It’s like “archetypes”-we don’t actually understand these things. We see placebo as kind of like you’re pretending, or you think it so it works… I think it’s a bit more complex than that.

What are you trying to achieve with the film?

I’ve always been a filmmaker. I went to art school, and got into making Super 8 films, and after that I worked with bands, then went on to do Exploding Cinema, trying to create a whole alternative culture around film making. Then I got involved in raves, VJaying, further away from film making.

Then I went through an awful crisis in my mid to late thirties. I was experimenting with all sorts of different substances, like a mad doctor, getting hits and misses, after not taking any for a long time. I started falling apart, and this very difficult crisis lasted on-and-off for a few years. During that I discovered ayahuasca, and I just started shooting film. I wasn’t even sure what I was doing. I was interested in shamanism, and always had been since reading Casteneda’s books as a teenager.

On one of my trips to Peru in 2001 I went with a camera to interview Pablo Amaringo, after talking to him before and realizing he knew an awful lot. But there was no real plan about what the film was going to be like. It evolved over a period of time. When I was working with a production company after coming back from Peru, I had all this footage, and I said I wanted to do something with it. The film came out of that process. I started to see that my story was actually part of the film, and that’s what I should be looking at.

Then I went out to Peru again with a cameraman, to get more footage, and to start documenting the experiences I was having much more comprehensively. I started thinking about how my story and experiences would be the best way for me to try and understand shamanism, the mythology and so on. Otherwise it was just “funny primitive people” doing weird shit out in the jungle, which we have no bridge to; I realized I was the bridge to this experience, and that this was a powerful way to try to understand this. Part of my healing has been to try and understand what these people are talking about.

So the film’s come about as a result of several different stories: their stories and folklore, the shamans over there; partly, my own story; and the stuff I brought to it from Ireland, folklore that I’d collected there, some of which seemed to resonate with the oral traditions around shamanism I was hearing around Pucallpa. All these elements gelled together as an idea, Stories on a Stick.

At the same time, with me the director in the film, I started thinking about the whole documentary form. It’s an interesting way of interacting with the documentary process, which is seen as being objective; in a way I was “going native”, crossing over a line. About a year after I started doing this, these mainstream films started appearing, like Supersize Me and American Splendor. You could see the whole idea of documentary breaking down, using reconstructions and so on like in Touching The Void. This gave me the confidence to really push the boundaries of what a documentary could be. I was really interested in playing with the form like this, and of course the film lent itself to this sort of experimentation because it was about psychedelic states, dreams, mythology, memory and the supernatural.

Putting yourself into the film, deconstructing and reconstructing your experiences… Did this relate to or grow out of the experience on ayahuasca, of having the different parts of your psyche laid out before you, with an observer part watching?

I hadn’t consciously thought of that, but now that you mention it I’d say there’s something interesting going on there. It’s quite a cubist film in that way, in that there are all these different perspectives—even down to the whole thing of working with special effects, trying to create these visual metaphors. There’s a mixture of the diary form, from my own diaries, written and video diaries; there’s my own memory, which is very elastic; and there’s the special effects, trying to reconstruct internal, subjective experiences and create visual metaphors. People have said you can’t reconstruct these things, and you can’t. But since humans started taking plants, going back to Palaeolithic caves, there’s been representations of the experience; whether it’s just dots pecked onto a cave wall, the entoptics, the swirls, whatever.

Maybe they knew they were falling short of representing the whole experience, but they still felt compelled to mark it.

All around the Amazon, the face painting, the weaving, the pottery, it’s all there, it’s everywhere, those designs are integrated into all aspects of their lives. They were creating metaphors, connecting everything. The stick of maize becomes the vertical shaft, which the shaman travels up and down to the upperworld and the underworld, which has a cross at its centre: the four directions, north, south, east and west, a map of human consciousness. It’s incredible how it all integrates, right down to how smoke becomes a snake, or a rope, or a vine, or a ladder. Things morph into other things. It integrates the world you live in. And that’s a powerful thing to do. Otherwise you’ve got a world that doesn’t make any sense, and that’s terrifying.