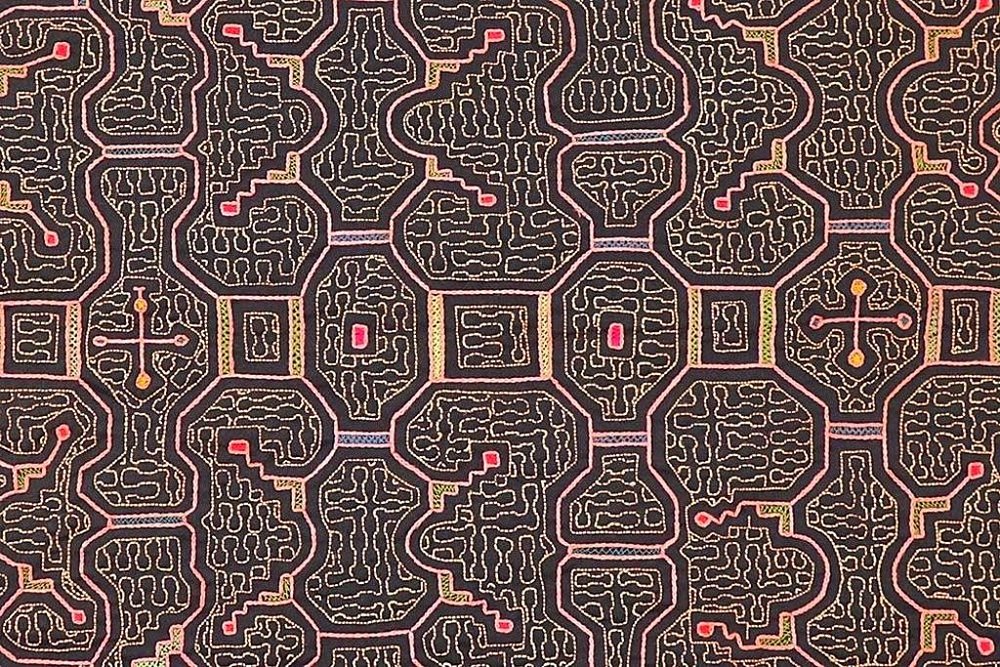

Art : Caapi Dreams by Donna Torres, 2016

© Donna Torres. Used with express permission. Visit her website at http://donnatorres.com/

This is an introductory beginners guide to several plants significantly connected to Ayahuasca shamanism. The forest is a ‘university of Life’ in which the shaman studies. Learning of the medicinal and spiritual qualities of each plant is part of the path of Vegetalismo.

Index

Banisteriopsis caapi – Ayahuasca, Oni, Yage

Psychotria Viridis -Chacruna

Cyperus – Piripiri

Nicotiana tabacum – Mapacho

Brugmansia suaveolens – Toé

Brunfelsia grandiflora – Manacá, Chiric sanango

Tynnanthus panurensis – Clavohuasca

Anadenanthera colubrina – Vilca

Salvia Divinorum – ska María Pastora

Mimosa Hostilis – Jurema

Bibliography

Banisteriopsis caapi – Ayahuasca, Oni, Yage

Indigenous names -yagé, huasca, rambi, shuri, ayahuasca, nishi oni, népe, xono, datém, kamarampi, Pindé, natema, iona, mii, nixi, pae, ka-hee, mi-hi, kuma-basere, etc

Taxonomy – Malpighiaceae (liana family)

Comments – The Banisteriopsis vine is a Malpighiaceous jungle liana found throughout Amazonian Perú, Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, western Brazil, and in portions of the Río Orinoco basin. It is employed across the Amazon basin for the treatment of disease and to access to the visionary or mythological world that provides revelation, blessing, healing, and ontological security (Dobkin De rios 1972, Andritsky 1984). Banisteriopsis caapi constitutes the common base ingredient of Ayahuasca, where it is ‘married’ with other plants, such as Psychotria viridis (chacruna) or Diplopterys cabrerana (chagropanga, chaliponga, oco-yage). Banisteriopsis caapi contains beta-carbolines that exhibit sedative, hypnotic, entheogenic, anti-depressant and monoamine oxidase inhibiting activity (McKenna DJ, Callaway JC, Grob CS 1996). Furthermore, the tea constitutes a complex and diverse indigenous pharmacopia, with many other plants added depending on specific medicinal or spiritual intentions. These include Brugmansia suaveolens (Toe), Brunfelsia grandiflora (Chiric sanango), Tynnanthus panurensis (Clavohuasca), Cyperus (Piripiri), Petivaria alliacea (Mucura, Anamu), and Mansoa hymenaeamanilkara (ajos sacha) among many others.

the Ayahuasca vine

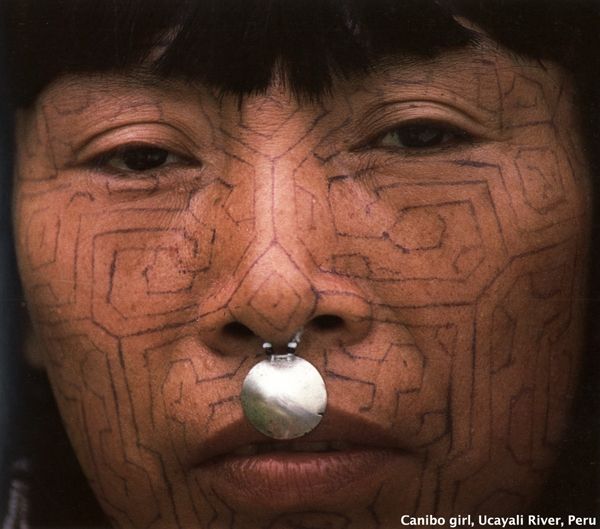

The use of Ayahuasca may well be primordial, its use extending back to the earliest aboriginal inhabitants of the region (Schultes and Hofman 1992). The oldest known object thought to relate to the use of ayahuasca is a ceremonial cup, hewn out of stone, with engraved ornamentation, which was found in the Pastaza culture of the Ecuadorean Amazon from 500 B.C. to 50 A.D (Naranjo, 1979, 1986). The patterning of traditional textiles, pottery and body art of various tribes can also be partially attributed to the visionary form constants of shamanic perceptions. The abundance of myths describing the origin of Ayahuasca as deeply intertwined cosmologically with the creation of the universe, earth, and tribal people, suggests a long history of human use. “… diverse indigenous groups all believe that the visionary vine is a vehicle which makes the primordial accessible to humanity.” (Luna, 2000). Ayahuasca is the most revered and respected sacred medicine of the New World.

Psychotria Viridis -Chacruna

Indigenous names – Chacruna, Amirucapanga, Kawa-kui, Rami-Appani

Indigenous names – Chacruna, Amirucapanga, Kawa-kui, Rami-Appani

Taxonomy – Rubiaceae (coffee family)

Comments – The foliage of Psychotria viridis is a principle admixture of Ayahuasca potions employed throughout Amazonian Peru, Ecuador and Brazil, prepared with Banisteriopsis caapi to make the ceremonial healing medicine Ayahuasca.

In Columbia, the plant Diplopterys cabrerana is often used instead. The combination of Yage vine with Chacruna is sometimes known as ‘The Marriage’ of ‘power’ (caapi) and ‘light’ (viridis), with Chacruna considered feminine in relation to the Grandfather Yage. The shamanic ‘mareación’ occasioned by ‘The Marriage’ is used for the purpose of shamanic healing, vision, and personal and collective integration.

Cyperus – Piripiri

Indigenous names – Piripiri, Ibenkiki.

Taxonomy – Family Cyperaceae (Sedge family)

Comments – People throughout the Amazon cultivate numerous varieties of sedges for a wide range of uses. The Machiguenga and Shuar use sedge rhizomes and bulb tops of Cyperus to treat headaches, fevers, cramps, dysentry, wounds, childbirth, and to improve weaving and hunting skills.

Cyperus species are congenitally infested with Balansia cyperi Edg. (Clavicipitaceae), a fungi shown to produce “several unidentified ergot alkaloids” (Plowman et al., 1990). Among these alkaloids, some of which are toxic, there are some, like ergonovine and ergine, known to have psychoactive properties (Bigwood et al., 1979).

In the Amazon basin, the Sharanahua Indians add powdered rhizomes of Cyperus to Ayahuasca potions (Schultes & Raffauf 1990). This may be Cyperus prolixus (Mckenna et al. 1986). Cyperus are also reported to be smoked in shamanistic practices (Plowman et al., 1990, Schultes & Raffuf 1990), and are also reportedly used in eyedrops by Shipibo-Conibo women in connection to the traditional Quiquin healing designs and textiles.

Nicotiana tabacum – Mapacho

Indigenous names – Mapacho, Lukux-ri (Yukuna); ye’-ma (Tariana); a’-li (Bare); e’-li (Baniwa); mu-lu’, pagári-mulé (Desano); kherm’-ba (Kofán); dé-oo-wé (Witoto)

Taxonomy – Solanaceae, Nightshade Family, Potato Family

Comments – Nicotiana are native in North and South America, especially in the Andes (45 species) and in Polynesia and Australia (21 species). Tobacco is one of the most important plants in the lives of all tribes of the northwest Amazon (Wilbert, 1987). Associated with purity, fertility and fecundity, it plays a major role in curative rituals and important tribal ceremonies. Recreational use is uncommon.

Tobacco is employed in the medical practices of many tribes. The Tukanoan peoples of the Vaupés often rub a decoction of the leaves briskly over sprains and bruises. Amongst the Witotos and Boras, fresh leaves are crushed and poulticed over boils and infected wounds. The Jivaros of Ecuador take tobacco juice therapeutically for indisposition, chills and snake bites, and also during war preparations, victory feasts and shamanic ritual.

Nicotiana is used across the Amazon “as a transformation agent side by side with Anadenanthera, Banisteriopsis, Trichocerus pachanoi… and Virola in the jaguar complex and lycanthropy in general” (Wilbert 1987). The ayahuasqueros of Perú mix tobacco juice with Ayahuasca, crushing the leaves and softening them with saliva, leaving the juice overnight in a hole cut into the trunk of the lupuna tree (Trichilia tocachcana), the sap of which drips into the tobacco juice. Amongst the western Tukanos of Colombia and Brazil, curanderos give their students tobacco juice to cause purging and shamanic journeying. Amongst the Quichua of Eudador, the aspiring shaman must apprentice with tobacco juice during their training.

One of the most widespread additives to Ayahuasca, the Shuar, Shipibo and Piro, Machigenga, Cocama, Barasana, Aguaruna and Campa vegetalista’s imbibe tobacco juice (of n.tabacum and n.rustica) or lick ‘ambil’ (an edible tobacco preparation) with Banisteriopsis Caapi (Wilbert 1997). Tobacco is also smoked in the ceremonies and curative rituals of certain tribes such as the Lamista, Shipibo, and mestizo curanderos, who blow smoke over the Ayahuasca brew and over the patients, combined with appropriate icaros.

This tobacco is virtually unrecognisable from commercial tobacco. It is without chemical treatment and additives, and has a fragrance that the Spirit of Ayahuasca is said to like (Luna & Amaringo 1991). Tobacco is fundamental to the world-view of the American shaman (Wilbert 1991).

Brugmansia suaveolens – Toé

Indigenous names – Toé; Floripondio; Maricahua; Campana; Borachero; Toa; Maikoa (Jivaro); Chuchupanda (Amahuaca); Aiipa (Amarakaeri); Haiiapa (Huachipaeri); Saaro (Machiquenga); Gayapa y Kanachijero (Piro-Yine); Kanachiari (Shipibo-Conibo), Angels Tears, Angels Trumpet.

Taxonomy – Solanaceae (Nightshade)

Comments – The family Solanaceae are the most widespread and widely used class of vision inducing plants (Ott 1996). Often called the ‘tree Daturas’, Brugmansia are now recognized by botanists as deserving of a distinct taxonomic status within the family Solanaceae. All species of the genus are native only to South America. Brugmansia suaveolens, a 10 foot tall flowering bush, grows in the tropical lowlands of the Amazon where it is used as a shamanic inebriant and as an Ayahuasca admixture (Schultes & Raffauf 1992). The shamanic use of Brugmansia is concentrated mainly in the west: along the Andean and Pacific fringe of the continent from Colombia down to southern Peru and the middle of Chile. The plants are widely traded for both their psychoactive properties and ornamental value. The Kamsa and Ingano people of the Sibundoy Valley in the Columbian Andes distribute a number of species throughout the Amazon.

Brugmansia is also sometimes used in conjunction with tobacco. The present-day Tzeltal Indians of Mexico smoke the dried leaves of B. suaveolens with Nicotiana rustica in order to obtain visions that indicate the cause of various diseases. The Jivaros use Brugmansia in initiation rituals to communicate with the ancestor spirits. The Jivaro Indians of eastern Ecuador and Peru used species of Brugmansia in a decoction which was taken as an enema by their warriors ‘to gain power and foretell the future’ (De Smet 1983). A Jivaro boy as young as six may take Brugmansia or Ayahuasca under the supervision of his father in order to create an ‘external soul’, a ‘psychic ‘organ’ capable of communicating with the ancestors through visionary experiences (Rudgley 2000).

The brugmansia genus is typically rich in anticholinergenic alkaloids, hyoscyamine, atropine, and scopolamine. Substances which block cholinergic transmission interfere with the operation of the parasympathetic nervous system, and may result in toxicity or death because of action on basic life-support functions (Winkelman 1999). Since tropane alkaloids are extremely toxic in very small amounts, curanderos use toé very cautiously, a local informant has written that only 1 leaf is used in an Ayahuasca tea to be consumed by 5-10 people. The use of Brugmansia for magical purposes is the province of skillful master curanderos only.

Brunfelsia grandiflora – Manacá, Chiric sanango

Indigenous names – Manacá, Manacán, Chiriguayuasa, Chiric sanango, Chuchuwasha, Manaka, Vegetable Mercury, Managá Caa, Gambá, Jeratacaca

Taxonomy – Family Solanaceae

Comments – Manacá is a medium sized shrubby tree growing up to 8 meters in height and is indigenous to the Amazon Rainforest. It can be found in the Amazon regions of Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Columbia and Venezuela. Manacá has a long history of indigenous use in the Rainforest as both a medicinal plant and a magical plant. It’s common name Manacá, comes from the Tupi Indians in Brazil, who named it after the most beautiful girl in the tribe, Manacán, because of its beautiful flowers.

The active constituents of Manacá include the alkaloids Manaceine and Manacine, scopoletin and Aesculetin. Manaceine and Manacine are thought to be responsible for stimulating the lymphatic system while Aesculetin has demonstrated analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities. Scopoletin is a well known phytochemical which has demonstrated analgesic, antiasthmatic, anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, antitumor, CNS-stimulant, cancer-preventive, hypoglycemic, hypotensive, myorelaxant, spasmolytic and uterosedative activity.

It is used within spiritual and medicinal contexts by many tribal peoples including the Kofan, Siona, Ingano, Runa and Shuar, who are known to add the bark, leaves or roots to Ayahuasca (Kohn 1992; Plowman 1977; Schultes and Raffauff 1990). It is also used alone as an entheogen by the Kofan and Siona-Secoya peoples. Shamans consider B. grandiflora a spiritual guide (Plowman 1977).

An informant has written that 2-3g per person is used in native contexts for stimulation of the lymphatic system and as an ayahuasca admixture. This herb can be dangerous in excessive doses.

Tynnanthus panurensis – Clavohuasca

Indigenous names – Manacá, Manacán, Chiriguayuasa, Chiric sanango, Chuchuwasha, Manaka, Vegetable Mercury, Managá Caa, Gambá, Jeratacaca

Taxonomy – Family Bignoniaceae

Comments – “Our informants believe that the spirits of these admixtures present themselves either during the hallucinations elicited by the beverage or in the dreams following the intoxication, and that they disclose to the initiate their pharmacological properties. Our informants also recognise the synergistic effect that sometimes occurs when several plants are taken together. This concept is based on the idea that these plants “know each other” or “go well together,” while other plants “do not like each other.” (D McKenna 1995)

Tynnanthus panurensis, Clavohuasca (‘clavo’ = ‘clove’ , ‘huasca’ = ‘vine’) is a large woody vine that grows up to 80 meters in length which is indigenous to the Amazon rainforest and other parts of tropical South America. The vine bark has a stong distinctive clove-like aroma, earning it common name, Clove Vine. The vine cross-section has a distinctive maltese cross corazon.

Besides the rubiaceous admixtures such as Psychotria Viridis almost always included in Ayahuasca, a host of admixtures are employed depending on the magical, ritual, or medical purposes for which the potion is being made and consumed (Schultes 1957; Pinkley 1969; Rivier and Lindgren 1972; Luna 1984; McKenna et al.1984). Clavohuasca is one such Ayahuasca admixture (Burman, Luna 1984),

Clavohuasca is traditionally prepared by macerating the vine bark and wood in alcohol or most commonly, the local sugar cane rum called aguardiente. In Brazilian herbal medicine, the plant is called Cipó Cravo and it is considered an excellent remedy for dyspepsia, difficult digestion, and intestinal gas (brewed as a water decoction) as well as an aphrodisiac (macerated in alcohol into a tincture). Indian tribes in the Amazon in both Peru (Shipibo-Conibo) and Brazil (Kayapo, and Assurini) highly regard Clavohuasca as an effective aphrodisiac for both men and women.

There is no published clinical studies as yet on Clavohuasca. Preliminary phytochemical analysis by Brazilian scientists have discovered an alkaloid they named “tinantina” as well as tannic acids, eugenol and other essential oils.

Anadenanthera colubrina – Vilca

Indigenous names – Vilca, Cebil (Argentina), Huilca, Angico preto (Brazil), Curupay-atá (Paraguay).

Taxonomy – Family Leguminosae

Comments – Anandenanthera colubrina is mimosa-like tree that occurs around N. Chile in the Andes, where Argentina & Bolivia meet. It can grow to 80 foot high and have a trunk diameter of up to 2-3 foot. The seeds of A.colubrina has been employed via snuff, enema and smoked preperations for medicinal and shamanistic purposes for ~4000 years by the Inca and other cultures of Argentina and Southern Peru, as evidenced by the presence of cebil seeds in preceramic levels (2130 B.C.) at Incacueva, a site in the northwest of Humahuaca in the Puna border of the Province of Jujuy, Argentina (M. L. Pochettino, A. R. Cortella, M. Ruiz. 1999).

The seeds of A. colubrina are still used to cure the sick, benefit and protect the community, and for oracular or divinatory purposes (Logan 2001), by the Mataco Indians of the Rio Bermejo and Rio Pilcomayo area of Argentina (Repke 1992; Torres 1992) where it is known as huilca or vilca and cébil (Altschul 1967).

In terms of it’s usage alongside Ayahuasca, it has been reported that “Tiwanakuans, like the Guahibo today, combined sniffing Anadenanthera with chewing the ayahuasca vine” (Beyer, referencing Torres & Repko, 2006, p. 73); and that “the Piaroa today, pounded shoots of the ayahuasca vine into a paste along with Anadenanthera seeds” (Rodd, 2002).

As well as the seeds, an exudate that is secreted from the leaf tips appears to exhibit entheogenic properties (Logan 2001). This exudate attracts ants which serves to protect the plant from predators. Plants need full sunlight and prefer well-drained soil. Let the soil dry completely between watering. A. colubrina can handle some short term freezing conditions.

Calea zacatechichi – Thle-pelakano

Indigenous names – Thle-pelakano (Leaf of God) , zacatechichi (bitter grass), “hoja madre” (mother’s leaf), Zacate de perro, ‘dream herb’.

Taxonomy – Family Compositae

Comments – Calea zacatechichi is a heavily branching shrub with triangular-ovate, coarsely toothed leaves 3/4-2 1/2 inc. (2-6.5 cm) long. The inflorescence is densely many-flowered (usually about 12). The plant grows from Mexico to Costa Rica in dry savannas and canyons (Schultes and Hoffmann, 1973).

The name of the species comes from Nahuatl “zacatechichi” which means “bitter grass” . Calea zacatechichi is very important in native herbal medicine, an infusion of the plant (roots. leaves and stem) is employed against gastrointestinal disorders, as an appetizer. cholagogue, cathartic. antidysentry remedy, and has also been reported to be an effective febrifuge. It is also utilized by the Chiapas and Chontal of Mexico as a shamanic plant. They call the herb ‘Tle-pelankano’ (leaf of God) and believe it facilitates divinatory messages during dreaming. When the cause of an illness needs to be identified, or a distant or lost person found, dry leaves of the plant are smoked, drunk as a tea, and put under the pillow before going to sleep.

“…zacatechichi administration appears to enhance the number and/or recollection of dreams during sleeping periods. The data are in agreement with the oneirogenic reputation of the plant among the Chontal Indians… Calea zacatechichi induces episodes of lively hypnagogic imagery during SWS stage I of sleep, a psychophysiological effect that would be the basis of the ethnobotanical use of the plant as an oneirogenic and oneiromantic agent. ” – Journal of Ethnopharmacology 18 (1986) 229-243 “Psychopharmacologic Analysis of an Alleged Oneirogenic Plant : Calea Zacatechichi” by Jose-Luis Diaz and Carlos M. Contreras

Petiveria alliacea – Mucura

Indigenous names – Mucura, Chanviro, Mikur-ka’a, Anamu, Tipi

Taxonomy – Phytolaccaceae

Comments – Petiveria alliacea is an herbaceous perennial that is indigenous to the Amazon Rainforest and can be found in other areas in Tropical America and Africa.

It has a long history in vegetalismo practices in herbal baths and as an ayahuasca (yage) admixture. Ritual amulets containing Mucura and Ajos Sacha are exchanged between partners. It also has uses as an analgesic, diuretic, emmenagogue, vermifuge, insecticide, and sedative. It is a purifying and protective plant. It is thought to protect against witchcraft and attacks from humans and animals. Traditionally is used as a herbal bath in a purifying cleansing ritual called ‘limpias’. An infusion of 2 grams of dried mucura is soaked overnight in a liter of water to wash off the ‘saladera’, a ‘salt’ or phlegm that lingers in the subtle body and is thought to cause bad luck.

Mansoa hymenaeamanilkara – Ajo Sacha

Indigenous names – Ajo Sacha, Lavender Garlic Vine, ajo macho, ajos del monte, bo’o-ho, be’o-ja, boens,frukutitei, niaboens, posatalu, pusanga, sacha ajo, shansque, boains.

The Spirit Woman of ‘Ajo Sacha’ by Yolanda Panduro & Don Francisco Montes Shuna.

Taxonomy – syn. Mansoa Alliacea, Bignoniaceae

Comments – Literally translated as “false” or “fake garlic”, ajo sacha is a vine-like tree whose leaves, when crushed, smell like garlic, with a hint of onion. Its leaves, bark, and roots have analgesic, antipyretic, and antirheumatic properties, and the preparations made from its parts can be used either orally or topically.

A revered plant teacher throughout the Amazon basin, Ajos Sacha traditionally is used as a herbal bath in a cleansing ritual called ‘limpias’. The curanderos prepare the leaves of Ajos Sacha by cutting them very carefully into tiny pieces, water is added, and the essence strained and collected into a vessel, often icaro’s are sung over it, and a little magnet is dropped inside the vessel, to add ‘strength’ to the preperation (Luna 1984). Then the client washes themselves with the liquid and rinses the mouth out to cleanse them of the saladera (salt), a phlegm that has accumilated in the organism, causing bad luck and ill health (Dobkin de Rios 1981). The vegetalista whistles the appropriate icaro over the patient whilst ‘painting’ the person with the liquid (Luna 1984).

Ajo sacha is used as an Ayahuasca admixture (Padoch and De Jong 1991, Luna 1984). Ayahuasca and other plants that have cathartic properties expel the phlegm from the organism. “Vegetalistas say that Ayahuasca is needed for cleansing all the flemosidades (phlegm formations) that accumulate in the intestines” (Luna 1984). It is used generally for sensibility and awareness, and Ajos Sacha is considered an ‘Amansador’, which means that people and animals will not harm the person who uses this plant. (Karsten 1964)

Salvia Divinorum – ska María Pastora

Indigenous names – ska Maria Pastora, hojas de la Pastora, Yerba María, pipiltzintzintli, hoja de adivinación (leaf of prophecy)

Taxonomy – Labiatae/Lamiaceae

Comments – Salvia divinorum is native to forest ravines and other humid areas of the Sierra Mazateca of Oaxaca, Mexico, between 750 m and 1500 m altitude. Ethnobotanist R. Gordon Wasson has proposed S.Divinorum is the ancient Aztec plant pipiltzinzintli. Leaves of Salvia divinorum are used for curing and divination by the Mazatec Indians who call the plant “the leaves of the shepherdess” ; this term could refer to a nature deity, as the biblical Mary was not a shepherdess.

Salvia divinorum is traditionally employed as quids amounting to 20 to 80 leaves, nibbled by the curandero, the patient (or apprentice) or both, depending on the situation. Following its ingestion the Shepherdess is supposed to guide the individual, but only in absolute quiet and darkness. The plant is also used as a “medicine” for ‘panzon de barrego’, a swollen belly caused by sorcery, as well as for headaches and rheumatism.

Mimosa hostilis – Jurema

Indigenous names –Vinho da Jurema, Jurema, Jurema Preta, Tepezcohuite, Tepescohuité, Arbre de peau, Ajucá, Caatinga

Taxonomy – Syn. Mimosa tenuiflora, Family Leguminosae

Comments – Mimosa Hostilis occurs from the vast Brasilian caatinga northward to the state of Oaxaca in southern Mexico (Barneby 1991). In Mexico the stem-bark is a well-known ethnomedicine. In 1984, in Mexico City, the explosion of a gas factory caused the death of 500 people and badly burned more than 5000. The hospitals and Red Cross sought an emergency treatment for the multitude of patients and turned to the ancient Mayan Tepezcohuite, which proved extremely successful.

In 1946, Brasilian microbiologist Oswaldo Gonçalves De Lima reported the shamanic use of ajucá or vinho da jurema among the Pancarurú Indians of Brejo dos Padres near Tacaratú in the valley of the Rio São Francisco in southern Pernambuco. Cold-water extractions of Jurema, with no other additives, is employed by numerous groups scattered sparsely over northeastern Brasil including the Xucurú of Serra de Ararobá in northern Pernambuco (Hohenthal 1952); Kariri-Shoko of Colegio near the mouth of the Rio São Francisco which demarcates the Alagoas/Sergipe border (Da Mota 1987); the Atikum of the Serra do Umã in western Pernambuco (De Azevedo Gronewald 1995); the Truká (Batista 1995).

Bibliography

Bibliography – Ayahuasca

Andritzky, W., Jan-Mar 1989; Sociopsychotherapeutic functions of ayahuasca healing in Amazonia. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs Vol 21 (No. 1) 77-89.

Brent, M. (2001). Ayahuasca, Religion and Nature. Lila : Transpersonal Shamanic Database.

DeKorne, Aardvark, & Trout 2000; Ayahuasca Analogs and Plant-Based Tryptamines. The Entheogen Review .

Dobkin de Rios M. 1972. Ayahuasca & It’s Mechanisms of Healing. From Visionary Vine: Hallucinogenic healing in the Peruvian Amazon. San Francisco: Chandler Publishing.

Hoffmann E, Keppel Hesselink and Yatra-W.M. da Silveira Barbosa. (2001) Effects of a Psychedelic, Tropical Tea, Ayahuasca, on the Electroencephalographic (EEG) Activity of the Human Brain During a Shamanistic Ritual. MAPS – Volume XI Number 1 Spring 2001.

Luis Eduardo Luna & Steven F. White., 2001. AYAHUASCA READER : Encounters with the Amazon’s Sacred Vine. Synergetic Press ISBN 0 907791 32 8

Luna, L E & Amaringo, P., 1991. Ayahuasca Visions : The Religious Iconography of a Peruvian Shaman. North Atlantic Press

Luna, L E. Vegetalismo : Shamanism among the Mestizon Population of the Peruvian Amazon. Almqvist & Wiksell Internaltional. Stockholm/Sweden.

Luna, L E. 1984. The Concept of Plants as Teachers among four Mestizo Shamans of Iquitos, Northeastern Peru. The Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 11 (1984) 135-156

Metzner, R, Ph.D. (editor)., 2000. Ayahuasca – Human Consciousness and the Spirits of Nature. Thunder’s Mouth Press, New York.

McKenna DJ, Callaway JC, Grob CS (1998), The scientific investigation of ayahuasca: a review of past and current research. The Heffter Review of Psychedelic Research, Vol 1, pp 65-77.

McKenna DJ, Callaway JC, Grob CS (1996), Human Psychopharmacology of Hoasca, A Plant Hallucinogen Used in Ritual Context in Brazil. The Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease Volume 184(2) February 1996 pp 86-94.

McKenna D, Towers GHN, Abott FS. 1984. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors in South American hallucinogenic plants: Tryptamine and beta-carboline constituents of ayahuasca. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 10:195-223.

Naranjo, P. 1986. “El ayahuasca en la arqueologica ecuatoriana”. America Indigena 46(1). Ott, J. (1994). Ayahuasca Analogues: Pangean Entheogens. Natural Products Co., Kennewick, WA.

Savinelli, A, Halpern J H, MD. (1995). MAOI Contraindications. MAPS – Volume 6 Number 1 Autumn 1995 – p. 58

Schultes RE, Hofmann A (1992) Plants of the gods: Their sacred, healing and hallucinogenic powers. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press.

Schultes RE, Raffauf RF (1992) Vine of the soul: Medicine men, their plants and rituals in the Colombian Amazonia. Oracle, AZ: Syngertic Press.

Shanon, B. Ph.D (1998). Ideas and Reflections Associated with Ayahuasca Visions. MAPS – Volume 8 Number 3 Autumn 1998.

Shanon, B. Ph.D 1999. “Ayahuasca visions: A comparative cognitive investigation,” Yearbook for Ethnomedicine and the Study of Consciousness 8 (in press). Edited by C. Rätsch & J. Baker. Berlin: VWB Verlag.

Topping, D,M. Ph.D. Professor Emeritus, University of Hawai’i. (1998). Ayahuasca and Cancer: One Man’s Experience. MAPS – Volume 8 Number 3 Autumn 1998 – pp. 22-26

Topping, D,M. Ph.D. Professor Emeritus, University of Hawai’i. (1999). Ayahuasca and Cancer: A Postscript. MAPS – Volume 9 Number 2 Summer 1999 – pp. 22-25

Bibliography – Cyperus – Piripiri

Schultes R.E & R.F Raffauf, 1990. “The Healing Forest : Medicinal and Toxic Plants of the Northwest Amazonia”. Dioscorides Press, Portland, OR.

Ott J., 1996, Pharmacotheon. Entheogenic drugs, their plant sources and history, 2° ed., Kennewick, CA, Natural Products.

Plowman T.C., A. Leuchtmann, C. Blanet & K. Clay, 1990, Significance of the Fungus Balansia cyperi Infecting Medicinal Species of Cyperus from Amazonia, Econ.Bot., 44:452-462.

Bigwood J., J. Ott, C. Thompson & P. Nelly, 1979, Entheogenic Effects of Ergonovine, J.Psyched.Drugs, 11:147-149.

Russo, Ethan B. M.D. Department of Neurosciences. 1996. “Schedule 1 Research Protocol: An Investigation of Psychedelic Plants and Compounds for Activity in Serotonin Receptor Assays for Headache Treatment and Prophylaxis”. From MAPS – Volume 7 Number 1 Winter 1996-97 – pp. 4-9.

McKenna, D.J. et al. 1986. “Ingredientes biodinamicos en las plantas que se mezclan al ayahuasca. Una farmacopea tradicional no investigada” America Indigena 46(1):73-99.

Bibliography -Nicotiana tabacum – Mapacho

“Mapacho” – Amazon Spiritquest Public Information Service

Ott ,Jonathon, “Pharmacotheon” pub. by: Natural Products co.

Schultes, R.E. and R.F. Raffauf. 1995. “The Healing Forest: medicinal and toxic plants of the northwest Amazonia”, Dioscorides Press, Portland, Or.. ISBN 0-931146-14-3

Wilbert, J. 1987. “Tobacco and Shamanism in South America”, Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

Wilbert, J. 1991. “Does pharmacology corroborate the nicotine therapy and practices of South American shamanism?” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 32 (1-3):179-186

A.L. Jussieu. “Mapacho Analysis, preparation, and use of Nicotiana tobaccum”. Historical, Ethno & Economic Botany Series Volume 2

Bibliography – Brugmansia suaveolens – Toé

Schultes RE, Raffauf RF 1992. “Vine of the soul: Medicine men, their plants and rituals in the Colombian Amazonia”. Oracle, AZ: Synergetic Press.

Schultes, R.E., and Raffauf, 1990. “The Healing Forest. Medicinal and Toxic Plants of the Northwest Amazonia”, R.F. Dioscorides Press, 1990.

Rudgley, R, 2000. “The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Substances”. Griffin Trade Paperback; ISBN: 0312263171

Ott ,Jonathan, 1996. “Pharmacotheon” pub. by: Natural Products co.

De Smet, P.A.G.M. 1983. “A Multidisciplinary overview of intoxicating enema rituals in the western hemisphere”. JouRnal Of Ethnopharmacology 9(2,3):129-166.

Bibliography – Brunfelsia grandiflora – Manacá, Chiric sanango

Schultes, R.E., and Raffauf, 1990. “The Healing Forest. Medicinal and Toxic Plants of the Northwest Amazonia”, R.F. Dioscorides Press, 1990.

Leslie Taylor, Personal field notes with Curandero Jose Guerra Cabrerra near the village of Tam Hisaco. September, 1997, with Curandera Consuela Garcia of the Ecuadorian Ashur tribe, April, 1997, and with Curandero Don Antonio Montero at ACEER, Peru. August 1996

Rios, Marlene Dbkin de, 1992, “Amazon Healer, The Life and Times of an Urban Shaman”. Avery Publishing Group, Carden City Park, NY

“Powerful and Unusual Herbs from the Amazon and China”, 1993. The World Preservation Society, Inc.

Ott ,Jonathan, “Pharmacotheon” pub. by: Natural Products co.

Plowman, T.C, 1977. “Brunfelsia in ethnomedicine” Botanical Museum Leaflets Harvard University 25(10):289-320

Plowman,T.C, 1980. “The genus Brunfelsia : A conspectus of the taxonomy and biogeography” In : Hawkes, J.G. et all. (Eds.) The Botany and Taxonomy of the Solancaceae. (Linnean Soc. SYmposium Ser. No. 7) Linean Soc., London, England. pp.475-491

Kohn, E.O. 1992. “Some Observations on the use of medicinal plants from primary and secondary growth by the Runa of eastern lowland Ecuador” Journal of Ethnobiology 12(1): 141-152

Biblography – Tynnanthus panurensis – Clavohuasca

Schultes, R.E., and Raffauf, 1990. “The Healing Forest. Medicinal and Toxic Plants of the Northwest Amazonia”, R.F. Dioscorides Press, 1990.

Dennis J. Mckenna, L. E. Luna, And G. N. Towers, 1995. “Biodynamic Constituents in Ayahuasca Admixture Plants: An Uninvestigated Folk Pharmacopoeia” From Ethnobotany Evolution of a Discipline. ISBN 0-931146-28-3. Copyright © 1995 Dioscorides Press.

Duke, James and Vasquez, Rudolfo, 1994. “Amazonian Ethnobotanical Dictionary”, CRC Press Inc.

James Duke, 1997. “The Green Pharmacy”, Rodale Press

Cruz, G.L. 1995. “Dicionario Das Plantas Uteis Do Brasil”, 5th ed., Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Bertrand 1995.

Ott ,Jonathan, “Pharmacotheon” pub. by: Natural Products co.

Luna, L,E. 1986. “Vegetalismo : Shamanism among the Mestizo Population of the Peruvian Amazon. Almqvist and Wiksell International, Stockholm, Sweden.

Rivier, L and J.E. Lindgren. 1972. “Ayahuasca, the South American hallucinogenic drink : An Ethnobotanical and chemical investigation”. Economic Botany 26(1):101-129.

Pinkley, H.V. 1969. “Plant admixtures to Ayahuasca, the South American hallucinogenic drink”. Lloydia 32(3):305-314.

Biblography – Calea Zacatechichi

Lilian Mayagoitia. Jose-luis Diaz And Carlos M. Contreras. “Psychopharmacologic Analysis Of An Alleged Oneirogenic Plant: Calea Zacatechichi” – Journal of Ethnopharmacology 18 (1986) 229-243 Eleavier Scientific Publishers Ireland Ltd.

Jose Luis Diaz, MD. “Ethnopharmacology and Taxonomy of Mexican Psychodysleptic Plants”. 1979

Bibliography – Ajo Sacha

Karsten, R. 1964. “Studies in the Religion of the South-American Indians East of the Andes.” Helsinki : Societas Scientiarum Fennica. Commentationes Humanarum Litterarum XXIX.1.

Padoch, C. and W. De Jong. 1991. “The house gardens of Santa Rosa : Diversity and variability in an Amazonian agricultural system”. Economic Botany 45(2):166-175.

Rios, Marlene Dobkin de, 1984, “Hallucinogens : Cross-Cultural Perspectives.” University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, NM.

Ott ,Jonathan, “Pharmacotheon” pub. by: Natural Products co.

Luna, L E. Vegetalismo : Shamanism among the Mestizon Population of the Peruvian Amazon. Almqvist & Wiksell Internaltional. Stockholm/Sweden.

Bibliography – Anadenanthera

Altschul, S. von R. (1964) A Taxonomic Study of the Genus Anadenanthera. Contrib. Gray Herb.193. 3-65

Califano, M. (1976) El Chamanismo Mataco. Scripta Ethnologicano. 3, pt. 2- 7-60

Furst, P. T. (1974) Hallucinogens in Precolumbian Art. In: King, E.M. and Traylor (Ed.) Art and Environment in Native America. Texas Technical University, Special Publications of the Museum, no. 7, pp. 55-102

Logan, N., (2000) Anadenanthera. Ethnobotany Special Event at Fort Lewis College

Ott ,Jonathon, Pharmacotheon pub. by: Natural Products co.

Pochettino M L. Cortella A R. Ruiz M. (1999) Hallucinogenic Snuff from Northwestern Argentina: Microscopial Identification of Anadenanthera colubrina var. cebil (Fabaceae) in Powdered Archeaological Material. Economic Botany 53(2)

Schultes, R. E., Vilca and its Use. (1967) In: Efron,D.H. (Ed.) Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs. Washington, D.C., US.Public Health Service Publ. no. 1645, pp. 307-314

Schultes, R. E., (1972) The Genus Anadenanthera in Amerindian Cultures. Cambridge, Mass., Botanical Museum, Harvard University.

Torres, C Manuel.(1996) Evidence for Antiquity of Entheogens in the Central Andes. Entheobotany: Shamanic Plant Science A Multi-Disciplinary Conference on Plants, Shamanism & Ecstatic States. 18-20 October, 1996 Palace of Fine Arts Theatre in San Francisco, CA.

Torres, C Manuel. (1992) Cohoba/DMT Snuffs. Botanical Preservation Corps Field Seminars, Audio recorded lecture.

Torres, C Manuel. (1999) The Use of Psychoactive Snuff Powders in Pre-Columbian San Pedro de Atacama, Chile. From ‘Visions That The Plants Gave Us. Richard F Brush Art Gallery.

Torres, C. M., Repke, D. B., Chan, K., McKenna, D., Llagostera, A., & Schultes, R. E. (1991). Snuff powders from pre-Hispanic San Pedro de Atacama: Chemical and contextual analysis. Current Anthropology, 32(5) 640-649.

Biblography – Salvia Divinorum

Valdes L.J., et al. 1983. “Ethnopharmacology of Ska Maria Pastora (Salvia divinorum, Epling and Jativa-M.)” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 7(3):287-312

Ott J., 1996, Pharmacotheon. Entheogenic drugs, their plant sources and history, 2° ed., Kennewick, CA, Natural Products.

Wasson, R.G. 1962. “A New Mexican psychotropic drug from the mint family” Botanical Museum Leaflets. Harvard University 20(3): 77-84.

Bibliography – Mimosa Hostilis

Ott ,Jonathon, Pharmacotheon pub. by: Natural Products co.

Indigenous names – Chacruna, Amirucapanga, Kawa-kui, Rami-Appani

Indigenous names – Chacruna, Amirucapanga, Kawa-kui, Rami-Appani